|

| About Alan |

| Tutorials |

| Free files |

| Win9x FAQs |

| E-mail Alan |

| |

| Articles |

| BIV articles |

| Archive |

| Other articles |

| Archive |

| |

|

|

|

VirtualBox:

A Free, Open Source Way to Run Windows and Linux on Your Intel Mac

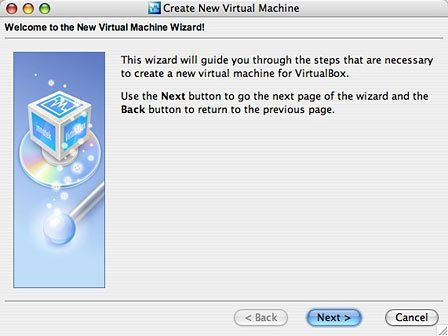

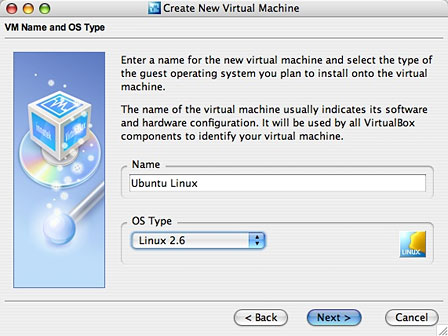

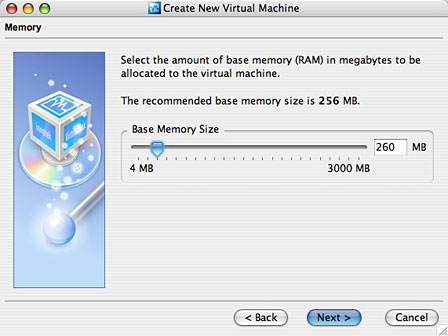

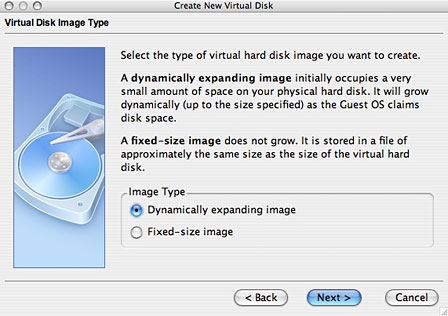

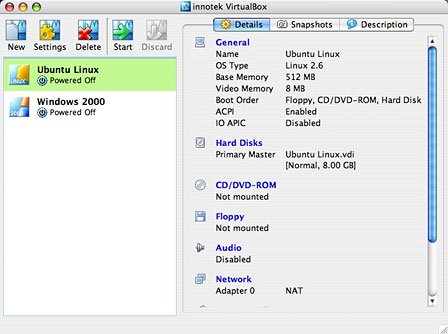

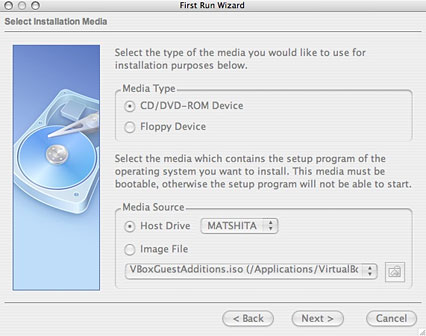

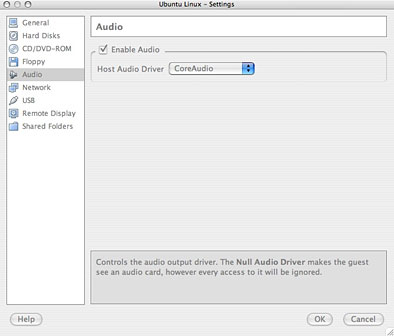

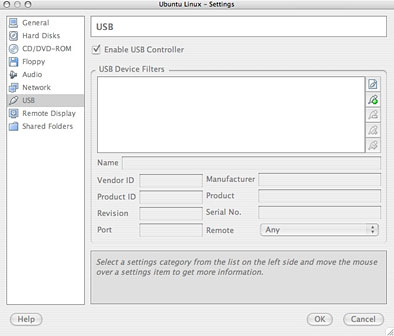

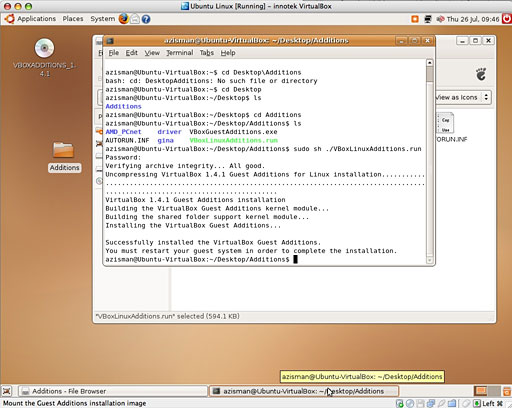

by Alan Zisman (c) 2007 First published in Low End Mac July 27 2007: Mac2Windows column Virtualization is a hot topic amongst computer users; it's getting a lot of interest from IT departments wanting to be able to run multiple servers on a single piece of hardware. In particular, this lets them run older software, such as applications designed for Microsoft's no-longer-supported Windows NT 4.0 Server, without having to keep an old computer in operation. Software developers and Web designers are able to test their creations on multiple platforms without having to actually have dedicated Windows, Linux, and Mac computers sitting on their desktops. Virtualization has been particularly of interest to Mac users; it allows them to run individual Windows applications (like Microsoft Access database) that lack Mac equivalents or to connect to Internet Explorer-only websites if necessary without having to hunt down a Windows PC. Apple's move to Intel-powered Macs has resulted in newer and better ways to run Windows, Linux, and other PC operating systems and software in virtual sessions on Macs. Virtualization on the Mac Parallels Desktop, now in version 3.0, is the best known and most widely used of this new generation of Mac virtualization products. VMware, long a leader in virtualization software for Windows and Linux is nearing the release of Fusion, its first product for the Mac. Competition has pushed both of these US$79 products to improve performance and increase features and ease of use. But these two commercial products aren't the only options for creating and running virtual computers on your Intel Mac. In January 2007, InnoTek released VirtualBox as a professional-level virtualization program that's available as open source software under the GNU Public License (GPL). As open source software, any interested can download, examine, and alter the source code. While corporate users are expected to buy licenses, it can be freely used by anyone for evaluation or personal use. VirtualBox is available in versions for Windows, Mac OS X (Intel), a growing number of Linux distributions, and other so-called host operating systems. I installed it onto a computer running Ubuntu Linux and onto an OS X-powered iMac. Note that while the current version 1.40 is an official release version for Windows and Linux, at the time of writing the Mac version is still in beta. (And, like Parallels and VMWare Fusion, it's only usable on Intel-powered Macs). The VirtualBox Mac installer notes the following beta issues: "Currently, we are aware of the following issues: "Note that we are planning to address all known issues." Since all these virtualization products end up doing the same thing - installing a 'Guest' operating system that runs on top of a 'Host' operating system - it's not surprising that they are similar to one another. Having worked with Parallels Desktop and VMware, along with older emulation software for PowerPC Macs like Virtual PC and Guest PC, getting VirtualBox up and running seemed pretty familiar. Users are walked through the process of creating a new virtual system with a relatively user-friendly wizard.  Users are asked to pick their desired Guest operating system from a list. While relatively straightforward for Windows, this may confuse wannabe Linux users: Rather than listing supported Linux distributions (Ubuntu, Fedora, SuSE, etc.), it lists Linux kernel versions; how many of us know which kernel is used with, say Ubuntu 7.04 vs. Ubuntu 6.10? Since I was installing the latest Ubuntu release, I picked the latest kernel listed, crossed my fingers, and hoped for the best. It seemed to work.  Users can accept the default settings for RAM and hard drive size or easily alter them - I increased the default RAM sizes to 512 MB for both Windows 2000 and Ubuntu 7.04 Linux.  Creating a virtual hard drive takes several steps, even if you're accepting the defaults. A nice feature - the default is to create a so-called dynamically installing drive image. With this, the virtual 8 GB drive I created for my Ubuntu Linux system won't automatically require that much space on my Mac's hard drive - instead, it only takes up as much space as is actually required by the files on the virtual drive (at the moment, 2.68 GB).  Once these are configured in the wizard, just pop in the install CD for your desired guest operating system and click Start. (Advanced users, which I'm not, can create scripts to replace the Wizard).  When you start up a virtual session for the first time, another wizard walks you through a few steps necessary to get the guest operating system installed. In particular, it checks whether you're installing from a 'real' CD or DVD in your computer's optical drive or whether you're using an image file. Most of us would probably be using a CD.  Once that's done, you're in business. Your guest operating system installer should load, and everything should run as normal, just as if you were installing onto a real, physical PC.  The virtualized system includes virtual hardware for a network adapter, sound adapter, video display adapter, etc. A few things to note: The sound adapter is turned off be default; you can easily turn it on, but be sure to pick the Core Audio option - the Null Audio option leaves sound turned off.  The display adapter uses 8 MB of RAM for video by default. While both Parallels and VMware are working on adding DirectX support for Windows gaming, you won't find VirtualBox a gaming powerhouse - even if you increase the amount of RAM set for video. The default 8 MB gave me 32-bit graphics in a 1024 x 768 window, which was fine for me. I haven't tested Windows Vista, but I suspect that regardless of the amount of video RAM set, it wouldn't support Vista's Aero graphics transparency and other eye candy. As with sound, USB support is disabled by default; it too can be turned on giving access to USB printers, and more. (Note that 'USB Memory Devices' such as flash drives are not supported in the OS X Beta version I tested.)  Just like Parallels and VMware virtual sessions, you're going to want to install "Additions" for improved functionality. Additions are included for Windows and Linux; they offer improved video and USB performance and smoothly integrate the mouse between the Mac and the guest desktop. (This can cause problems, and once installed it can be turned on or off - when this is not installed or turned off, users need to press the left Command key to get access to the mouse for the Mac.) The Additions can be installed from the program's Devices menu; once chosen, a CD image is loaded and appears as a drive, ready to run. The Windows additions installed without a hitch in my test Windows 2000 guest OS. I had to do a bit of fussing to make the Linux additions install on my Ubuntu session, however. Double-clicking on the VBoxLinuxAdditions.run file tried to load it in a text editor rather than running the file. In the end, I copied the contents of the virtual CD to a new folder on my desktop, opened a Terminal session, moved to that folder, and from the command line typed: Sudo sh ./VBoxLinuxAdditions.run After prompting for my password, the Additions installer ran. (Linux gurus probably know more elegant ways to make this work).  While the Parallels and VMware additions provide drag-and-drop between the guest OS desktop and the Mac desktop, VirtualBox lacks a similar feature. As well, the software promises the ability to set up Shared Folders - designated folders on the Mac that will appear as virtual drives on Windows or Linux virtual systems. The documentation tries to walk users through steps required to mount these virtual drives in Windows and Linux, but this needs to be made more automated. In any event, I couldn't get it to work - this seems to be what the beta warning quoted above meant by 'Internal Networking'. As a result, it wasn't as easy to move files between my Mac and my virtual sessions as it is using the commercial virtualization programs. Performance seemed fine - as with Parallels and VMware, virtualized sessions running on an Intel Mac seem to work at nearly full speed . . . at least if you've got enough RAM to throw at them. I've got 2 GB of RAM on this iMac; that lets me share 512 MB of it with my virtualized PC operating systems. If you already own a copy of Parallels Desktop, VirtualBox probably offers nothing new. But if you've got an Intel Mac and want to try out Windows, Linux, or some other PC operating system, this free and open source virtualization software can be a usable and attractive way to do it. It lacks some of the cutting-edge features of Parallels or VMware (such as Parallels' Coherence Mode or the ability to run a Boot Camp installation as a virtual session), yet it's an impressive piece of software. And the price is right!  |

|

|

|

|

| Alan Zisman is a Vancouver educator, writer, and computer specialist. He can be reached at E-mail Alan |