|

| About Alan |

| Tutorials |

| Free files |

| Win9x FAQs |

| E-mail Alan |

| |

| Articles |

| BIV articles |

| Archive |

| Other articles |

| Archive |

| |

|

|

|

|

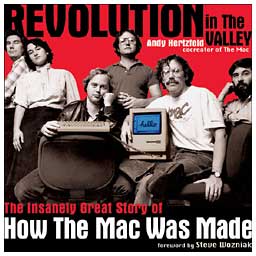

Revolution

in the Valley: The People and Stories Behind the Macintosh

by Alan Zisman (c) 2004 First published in Low End Mac February 8, 2005 Every child, I think, likes to hear stories about his or her birth and infancy. Sit down with their parents and look at baby photos. Many families assemble 'baby books', combining photos and reminiscences and more. The Mac was developed in the period 1979 to 1984 - the same period that my children were born. Andy Herzfeld is arguably one of the Mac's parents; buying an Apple II in January 1978, he became obsessed with it. Teaching himself 6502 assembly language, he quit grad school in August 1979 to become a systems programmer at Apple. There he heard about Jef Raskin's project to create a low-cost easy-to-use personal computer and got himself assigned to the team in February 1981, shortly after Steve Jobs replaced Raskin as the team leader. On the Macintosh team, Herzfeld worked on the operating system, its underlying Toolbox, and many of the original Desk Accessories. Leaving Apple after the Mac's release, he went on to found Radius and General Magic. He began writing down his stories of the birth of the Mac and began posting them online at www.folklore.org while soliciting contributions from other original Mac team members.  Revolution

in the Valley (O'Reilly, US$24.95, CDN$36.95) is an

assembly of

reminiscences in book form, mostly from Herzfeld, but also with

contributions from team members Steve Capps, Donn Denman, Bruce Horn,

and Susan Kare. Like a family's baby book, it's lavishly illustrated

with photos showing the Mac's parents (with hair and clothing that

could have been me in my children's baby books). Revolution

in the Valley (O'Reilly, US$24.95, CDN$36.95) is an

assembly of

reminiscences in book form, mostly from Herzfeld, but also with

contributions from team members Steve Capps, Donn Denman, Bruce Horn,

and Susan Kare. Like a family's baby book, it's lavishly illustrated

with photos showing the Mac's parents (with hair and clothing that

could have been me in my children's baby books).For any Mac-owner interested in his or her technological roots, this book is a really fun read. Herzfeld brings to life the people and the project; the stories move beyond the technical issues to highlight the culture of Apple in which it all took place. Read, for example, "It's the Moustache that Matters", how Burrell Smith, frustrated at being considered a 'lowly service technician' realized all the company's hardware engineers had prominent moustaches. After growing his own, he was quickly 'promoted to… full-fledged engineer'. Herzfeld considers relatively unknown Burrell Smith one of the true 'fathers of the Macintosh' for a series of innovative hardware designs.  Herzfeld's

anecdotes highlights the long and difficult birth process of the

Macintosh - how it started off in the shadow of older siblings like the

Apple II and the far larger Lisa development effort. (Lisa developer

Larry Tessler stalked out of a joint team meeting grumbling, "Tell

Steve that I think he's destroying Apple"). Relations with Bill Gates

and Microsoft. (Gates responded to Jobs' November 1983 accusations that

"You're ripping us off!" and "We both had this rich neighbor named

Xerox and I broke into his house to steal the TV set only to find that

you'd already stolen it"). Fights with Steve, especially as the Mac

grew from what Raskin had wanted to be a $500 computer to one targeted

for $1,500 and that eventually went on sale for $2,495. How even the

Puzzle desk accessory could become controversial. Herzfeld's

anecdotes highlights the long and difficult birth process of the

Macintosh - how it started off in the shadow of older siblings like the

Apple II and the far larger Lisa development effort. (Lisa developer

Larry Tessler stalked out of a joint team meeting grumbling, "Tell

Steve that I think he's destroying Apple"). Relations with Bill Gates

and Microsoft. (Gates responded to Jobs' November 1983 accusations that

"You're ripping us off!" and "We both had this rich neighbor named

Xerox and I broke into his house to steal the TV set only to find that

you'd already stolen it"). Fights with Steve, especially as the Mac

grew from what Raskin had wanted to be a $500 computer to one targeted

for $1,500 and that eventually went on sale for $2,495. How even the

Puzzle desk accessory could become controversial.Jobs always insisted that "real artists ship", and in January 1984 the Mac was finally ready (or as ready as a 128 KB system that really needed 512 KB would ever be). Burrell and Andy get their pictures in Newsweek and get recognized by the flight attendant while flying to Boston. With the product release, the stories get sadder as team members move on and out; by the beginning of 1985, Burrell Smith had quit Apple and Herzfeld had taken a leave of absence from which he would never really return. Even Steve Jobs would be forced out of Apple. But as Herzfeld closes the book, "the urgency, ambition, passion for excellence, artistic pride, and irreverent humor of the original Macintosh teach infused the product and energized a generation of developers and customers with the Macintosh spirit, which continues to inspire more than 20 years later". |

|

|

|

|

| Alan Zisman is a Vancouver educator, writer, and computer specialist. He can be reached at E-mail Alan |